Right now bots are primarily annoyances; 98% are spammers delivering often commercial come-ons via inscrutable language meant to evade anti-spam algorithms.

But some bots are more playful—intentional or unintentional performance art. Some recent examples that have bubbled up into the public consciousness include poetic e-book spammer turned subversive art project @Horse_ebooks and playful Twitter bot-makers Ranjit Bhatnagar and Darius Kazemi.

In less than three weeks you can be looking at things differently, more creatively, if you

— Horse ebooks (@Horse_ebooks) September 22, 2013

Bhatnagar’s @Pentametron finds a tweet inadvertently written in iambic pentameter and then finds another with a rhyming final syllable.

It’s never gonna happen anyway

— Mark Petronella (@MarkPetronella) February 7, 2014

Dang everybody’s birthday is today

— ☯❥❃ îce (@isisnatasha3) February 7, 2014

Kazemi’s @TwoHeadlines scans the web for headlines and mashes up two at a time, with results that sound inadvertently plausible.

Husky men melt down in 2nd half, lose to Wall Street, 78-69

— Two Headlines (@TwoHeadlines) February 7, 2014

Follow @robotuaries and it will occasionally tweet out a fake twitter obituary for you.

Erica Heinz, inspector, passed today at 114 following a fencing accident. Erica was residing in Fresno, California. /@ericaheinz

— Robotuaries (@robotuaries) February 7, 2014

While these bots amuse, others are useful, keyed to stock market movements or weather conditions. New York Times senior software architect Jacob Harris has created iron_ebooks, a utility that allows you to create “a _ebooks account tweets derived from a regular twitter account,” effectively giving you a bizarro version of your twitter self for you to observe and enjoy.

But a 2004 article by the NYT public editor rejected the legacy of a “Newspaper of Record” http://t.co/2Z3fWiKUTT

— Jacob Harris (@harrisj) February 7, 2014

He wasn’t wearing the suit which is the only Internet left.

— harrisj_ebooks (@harrisj_ebooks) February 7, 2014

@tofu_product does the same, but you have to ping it first.

@cmaxmagee I think those pop-up… You know that celebrated novelist Scientific paper. I’m all happened so fast.

— tofu (@tofu_product) December 7, 2013

These are rudimentary creatures, but even at this early stage they appear capable of poetry that can elicit the same reactions that traditional (i.e. human-created) poetry is intended to elicit. In the controlled world of Twitter, each bot performs its proscribed function, but what could future bots do?

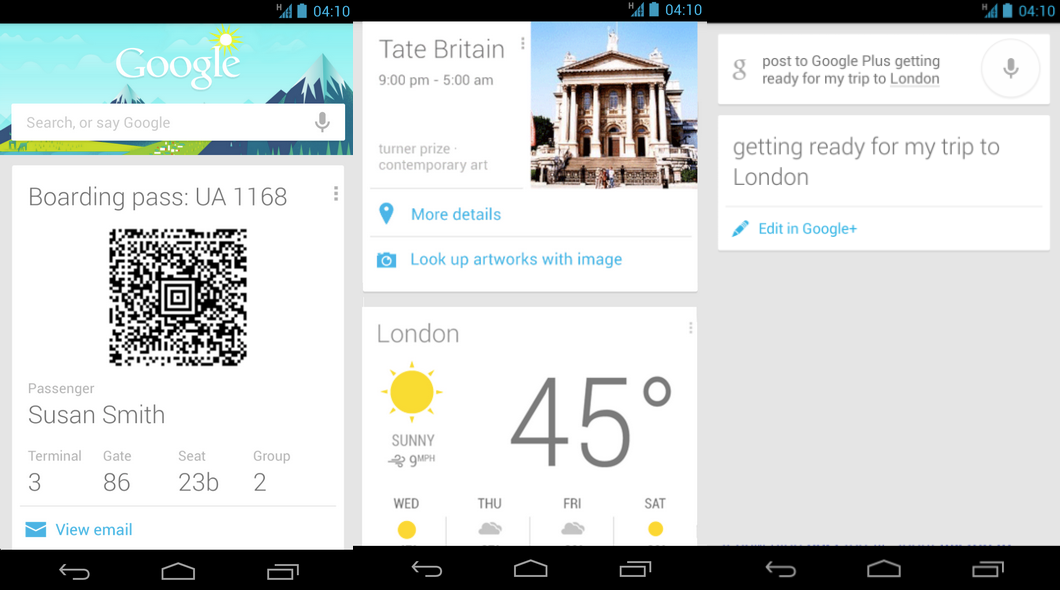

Certainly there are whole business models built on creating bots that are meant to learn our habits and help us in our daily lives (including, of course, pushing advertising our way.) Google Now is a leading-edge example of this. Even now, it’s offering me things to do nearby, giving me the weather here in Arizona and at home in New Jersey and showing me links to new articles on a variety of websites it knows I read.

Here’s someone else’s Google Now:

But might there also be promise in these bots in the worlds of art and literature? To take the Twitter example, could a bot learn enough to send me bespoke bits of poetry or personalized aphorism that it knows will elevate my mind and mood?

What about a bot that breaks the 140-character bounds of Twitter to send me personalized machine-generated art, snippets of music, or found and remixed narrative, all riffing on cues found in my online travels?

A pet bot just for me that sends me art made just for me.