Dr. Anouk Lang and Scott Selisker list the questions that their group have formed while writing about digital textual communities.

Knowledge Systems

The Body of the Text: When Materiality is No Longer Marginal

StandardGiven that, as I mentioned in my last piece, and as Sally Ball touches on in her second missive, some writers fear new media and digital publishing, concerned both about the sustainability of Kindle, iPad, and Nook platforms and over whether an e-book will “respect” their line breaks and, by extension, authorial intent, where is the real innovation happening in digital writing and publishing? Which experiments look promising for the potentials of digital storytelling?

Publishers have embraced the enhanced e-book as the future, embedding additional materials around a text (like bonus features on a Laserdisc or DVD). These materials can certainly deepen the reading experience, but they are predicated on our interest in interviews, videos, typescripts, and manuscript editions of a given work (I do, actually, want this material when reading Shakespeare or watching a Merce Cunningham dance). But such material remains paratextual, it is extra, rather than being integral.

Some of the most interesting experiments in the book and bookishness are those in which form and content interlink—as they do in the artist’s book—treating the object as an interface we do not simply look through or beyond (Michael Simeone informs me that when we read, in fact, our eyes are literally focused on a point just beyond the surface of the page). These projects embrace the affordances (and work with the constraints) of digital platforms to create “books” that engage the act of reading as a physical, embodied experience, even when mediated through a screen. I am interested in reading experiences that embrace embodied (or haptic) reading via touch, gesture, and sound (especially interactive binaural audio). These projects are not “the future” of the book, but they are forays into the present moment, and experiments at the edge of possibility—immersive experiences that do not pretend reading is a disembodied experience, either on the part of the reader or the text itself (which, of course, has a body of its own).

I’m especially excited about Samantha Gorman and Danny Cannizzaro’s forthcoming Pry, a novel for iPad about a soldier dealing with PTSD whose memories and imagination are layered vividly upon one another in a narrative that is itself a palimpsest of video, text, and sound. Pry takes advantage of the potential of the iPad to facilitate alternative approaches to storytelling. Not a “book,” “game,” or “film,” the project encompasses aspects of all three, creating an immersive (not to mention beautifully-designed) reading experience. Perhaps more importantly to me, Pry makes the medium through which readers encounter it part of the text. Nothing is paratextual, all is integral to the work. By prying open the text with her fingertips, the reader goes deeper into the protagonist’s subconscious, learning more about why James has hidden certain memories away and masked others with imagined experience. Elsewhere, one can force him to open his eyes and confront the external world, which he can only do in bursts due to an injury about which we learn as the story unfolds (or as we unfold it).

[vimeo vimeourl=”78973518″ ][/vimeo]

Erik Loyer’s Opertoon has put out some of the most sophisticated app-based reading experiences I have seen, including “Strange Rain,” in which the reader can control the first-person speaker’s meditative state through touch as he watches the sky during a downpour. Opertoon recently ventured into gesture-based reading with Breathing Room, a project for Leap Motion that allows the reader to navigate a landscape with a wave of the hand. Unlike visions of heads-up augmented reality interfaces that act like invisible screens (drag items from one place to another with your hands, double click with your fingertips), this work uses gesture as a metaphor for the act of reading itself (or this is how I read the interface): when you wave your hand, a gust of wind tosses the trees onscreen, clouds drift and shift depending on the speed of your movement, and the sound of a breath suggests the landscape itself is breathing, the reader providing the oxygen that activates the text. Loyer describes the work as a graphic novel, in part because the images and text onscreen appear in panels that suggest time’s passage through juxtaposition. One can reverse time, however, dialing back the clock by spiraling one’s finger in space, a beautiful and rewarding experience in which the role of the reader in traversing a text becomes tactile and present.

[youtube youtubeurl=”01Kf9T7o2Zs” ][/youtube]

Even as publishers experiment with enhanced e-books that include a range of bells and whistles built around the text, these creators are integrating them into the narrative and aesthetic experience. These innovations are not driven by market concerns, but by the desire to tell specific kinds of stories using the material at hand, whether that be a beautiful accordion fold-out book like Anne Carson’s Nox, which Sally Ball has described, or in a short story we navigate through spatialized binaural sound. I admire the way the interface is integral to the work in both of the cases described above, and I am reminded of Johanna Drucker’s claim that the book is better thought of as a “call” to a storage mechanism that can take many different forms (2013). Or, as Craig Dworkin puts it in No Medium (2013):

As much acts of interpretation as material things, as much processes as objects, media are not merely storage mechanisms somehow independent of the acts of reading or recognizing the signs they record.

It’s not that the medium is the message, but that the message is aware of its medium and its reader, working with and against the technical supports that underlie it. Creative practices can be invigorated by these constraints, particularly if they avoid the trap of thinking of reading, in any form, as immaterial.

My trajectory in these essays/posts/parries has been from the immaterial to the material, from the way cut and paste scraping facilitates the printing of unpublishable texts to app-based books that integrate their interface into their narratives. Or is it the other way around? Those first books take part in the tradition of the artist’s book as democratic multiple, they give material form to work that could have remained purely conceptual. Perhaps immateriality does not exist at all, even in the sort of “asocial” reading Dennis Tenen describes, where it feels as though the world beyond the text has disappeared. The body of the reader and the body of the book may be taken for granted, but they never disappear, leaving print and digital reading intertwined by material threads.

Books, Books Everywhere and Not a Drop to Drink

StandardA significant impediment for a reader considering whether to enter into the world of a book is that it is resource-intensive. As C. Max Magee discussed, books are expensive in “time and emotional energy.” The overall commitment is significant, and perhaps even more importantly, the commitment required to sample is high too. Spending an hour and a half reading a book you decide you don’t like is a deeply unpleasant experience, and frequently the reader quantifies that loss in terms of dollars than time: “I can’t believe I wasted $15 on this piece of crap.” A book you don’t want to read is worse than the absence of value, it destroys value (subjectively, of course).

One ramification is that the price of a book has to be radically discounted in order to persuade a reader to take a risk on something that could prove to be a negative experience. Dollar for dollar, a book is the cheapest form of narrative cultural experience there is, cheaper than music or film, and the perceived value, in the consumer’s mind, of content in digital format exacerbates the situation, putting even more downward pressure on pricing. The shift in consumption patterns away from ownership towards an access model, one driven by companies like Netflix in films, and by Spotify, Pandora, Last.fm, etc. in music creates yet more pressure. Indeed, in one respect, piracy means that all content is now, in effect, free, if you know how and where to look.

Nevertheless, the cost denominated in time and emotional energy remains as high as ever, higher if you consider that we are now swimming in content. Almost all platform innovation around content in the past five hundred years has occurred at the level of supply, whereas relatively little effort has been expended figuring out how to integrate all the stories we’re now actively telling. Probably the greatest effort has been expended by search engines around finding things you know you’re looking for, and social networks in seeking to organize the output of social activity, whether than activity is expressed in short bursts of words, or in pictures and short videos. But little effort has been expended on the largest and most demanding agglomerations of words, and on considering how to permit serendipity. Serendipity seems to require a sense of an encounter with the unexpected which is difficult to engender when we expect to have stories flowing by us throughout space and time.

The primary new platform innovation in books in 2013-2014 has been the subscription service, which seeks to apply the film/TV/music paradigm shift: a shift toward paid streaming subscription and away from both advertising-supported analog streaming from broadcast radio and TV and away from pay-per-download models like iTunes.

Currently, however, these services—the most discussed are Oyster and Scribd—focus on acquiring the latest possible libraries of content (each tout 100,000+ titles) and the lowest price ($9.99 and $8.99 respectively). However, with so much content in the world, more than any human alive could even name, never mind consume, and with most of it available either for free already or easily hackable, what value could such services possibly provide a reader?

My belief is that the power of any such service will inhere less in its ability to make more reading available more cheaply, and more in its ability to help us integrate reading into our daily lives. How this will happen is probably the determining factor in both how these platforms will evolve and the extent to which people will migrate to these reading services from other modes of of acquiring content for reading. I’m now working for a service called Byliner which shares with Oyster and Scribd a library model and a monthly subscription fee. However, it is also exploring ways to structure the library in a manner than enables a satisfying journey through all the stories. In this regard it has one advantage over Oyster and Scribd which is that it began life as a publisher of stories that can be read, typically, in 30-40 minutes, with stories (fiction and narrative nonfiction) ranging in length from 5,000 to 20,000 words. As such, the reader is not called up in each instance to embark on a long, potentially unpleasant journey—the fact that the stories are shorter than full-length books allow the reader to nibble her way through and, if we are able to serve her up successive stories that appeal, we’re able, ideally, to bring about a progressive sense of depth. A different experience we’re exploring is to select five stories, around a particular theme, say Genius, or Hustle, or Lust, and send those to subscribers once a week. So the first structure is akin to a reader journeying through the City of Stories, while the second operates more like a wine club, delivering weekly a set of new stories to read.

Regardless of how these various enterprises evolve, their existence signifies a positive development in the business of digital content, in that they do not require the enormous number of users that large-scale advertising-driven corporations need to survive. Stories of a significant length do not interest advertisers, since an individual serious narrative is never going to attract millions of readers. So a model wherein there is predictable recurring revenue, based on readers looking for precisely that, is a positive outcome for the reading-writing ecosystem overall.

Digital Textual Communities as Deep Maps: A Case Study

Standard For our third and final sprint, our Digital Textual Communities group has opted to produce a series of case studies of online communities that each of us belongs to, in order to give an insider’s perspective (or an emic approach, to be technical) about what it was like, in early 2014, to participate in these spaces. Our definition of a digital textual community has been kept deliberately broad, and resonates with what we have been calling the “ambient text”—the state of being surrounded by a flow of digital text, whether in the form of the Gchat windows that pop up unbidden on your laptop while you are attempting to concentrate on something else, the Twitter conversations that you follow while waiting for the lights to change, and the “old media” textual manifestations such as the advertisements at the bus stop or the book that you carry to read on the bus.

For our third and final sprint, our Digital Textual Communities group has opted to produce a series of case studies of online communities that each of us belongs to, in order to give an insider’s perspective (or an emic approach, to be technical) about what it was like, in early 2014, to participate in these spaces. Our definition of a digital textual community has been kept deliberately broad, and resonates with what we have been calling the “ambient text”—the state of being surrounded by a flow of digital text, whether in the form of the Gchat windows that pop up unbidden on your laptop while you are attempting to concentrate on something else, the Twitter conversations that you follow while waiting for the lights to change, and the “old media” textual manifestations such as the advertisements at the bus stop or the book that you carry to read on the bus.

I have chosen to write about my neighborhood social network, a digital textual community that I have belonged to since its inception. To keep it anonymous, I’ll give it the pseudonym NorthLondon.org. This site has been in existence for somewhere between five and ten years, and was set up by a private individual with no links to the local government authority or existing community groups. It is sustained by the ongoing care and attention of its founder and a small group of dedicated moderators, and has won international awards for its contributions to improving the neighborhood. Its membership currently stands at over seven thousand. It is not a textual community in the sense of gathering together people to discuss texts, but it is a platform on which communication with others is done almost entirely through text. Participation in it involves, of course, an aspect of identity management. I myself have two identities on the site: a primary one, which my friends know is me, and another more anonymous one for activities that I don’t want tied to my primary identity (usually for security reasons, so as not to give away where exactly I live). I think the site is worth writing about in this context because it is unusual for a social network in that a larger-than-normal proportion of its members have met in real life, evident from the number of events such as pub meet-ups that are organized, and the many threads in which individuals arrange to meet in order to loan each other equipment, pet-sit for one another, swap plant seeds, and so forth. There is some disagreement on the threads, and a small amount of trolling, but for a digital community there is a generally high level of civility, which I put down to the fact that participants are aware that there is a good chance they will know, and be known by, at least some of their interlocutors in real life.

What is it like to belong to this community? I’m wary of waxing techno-utopian, but I feel more at home in my neighborhood than I have in any place that I’ve ever lived, including the sleepy suburb of Sydney where I spent fifteen-odd years as a kid, and NorthLondon.org is at the very top of the list of reasons why. It tells me what is going on. It helps me to find people whose interests match mine. It has helped me to find people who have been happy to lend me various pieces of home hardware equipment, and to lend out various things myself; to uncover local knowledge about who is best at fixing a leaking roof and where the go-to places are for taking small children on rainy days. Through it, I found a nanny share, and a spare flat for visiting friends to stay in. My partner found a cricket team, and through that a group of friends. On my way to and from the tube station and the corner store, I pass people who I know and who will smile at me—a rarity on the mean streets of the capital!—because we have encountered each other first via NorthLondon.org. London has a reputation as a large, hostile city, in a country of famously reserved and unfriendly people, but the virtual community that has grown around this site has managed to cut across many of the social barriers we tend to throw up around ourselves, often for good reasons, in an overcrowded urban environment.

Rising above the personal to the communal level, other good things have been brought about by the site. There has been a great deal of local campaigning, some of its successful, to fix local problems from the mundane (litter and traffic) to the substantial (mistakes made by the local council, which have been pointed out and rectified). Recently, in a high-octane thread (which the writers of Law & Order should totally make into a storyline; I look forward to hearing from them with a proposal to consult), some muggers were reported to be operating along a particular stretch at a particular time of night. Thanks to reports by site members (and, it appears, by police picking up information by lurking on the site) the suspects were caught in a police sting.

One of my favorite occurrences is when a site member comes across a historical document (sometimes by knocking down a Victorian wall in their house and finding it among the rubble) and posts about it. It may be, say, a list of names of residents who lived in a particular road in the 1940s, or a photograph of a road which had just been bombed in the war. This generates a flurry of responses as current residents chime in, asking about who lived in their house, or adding details about the photo. The site provides a platform for recuperating, sharing, and preserving an oral history of sorts about the area that might otherwise be lost. I love learning things about my adopted city, but even more than this I love seeing my neighbors engaging with these historical texts, speculating about the past, making connections, and generating meaning in co-operative ways that are more than a little redolent of the way readers engage with books and with each other. I read those threads with delight, and I see the people who have posted on them in the pub, or walking their kids to school. The many threads of this sort that are woven together on NorthLondon.org make me think of my neighborhood as a text. Sometimes this textuality is almost literal: the sidewalks on one half of my road differ from those on the other half, and one day I discovered from NorthLondon.org that this was due to a historical boundary between local authorities, who had different means of upkeep for their roads. That historical boundary has long ceased to exist, but its traces are still visible in the built environment, and every time I pass them I can read London’s shifting political divisions in the ground under my feet. The digital community, which you could term a geographical paratext, brings the local environment to life in unexpected ways.

Some notes about the interface, as we are in part writing this as a quasi-historical account of what participation in such online communities entails. Much of the site’s activity consists of threaded discussions; those who post in them are informed of updates by email (and these notifications can be turned off). Members can post events; there are groups to which one can sign up in order to be kept abreast of activities in that group. Many members use real names and actual photos of themselves for avatars (I choose not to). As is standard for online social networks, there has been a fair degree of grumbling about the site’s interface, and from time to time moderators respond with changes. There is an automated system whereby the first dozen or so words of new forum posts are sent out on Twitter, meaning that it’s possible to discern the presence of content that moderators have decided to delete. Moderators’ decisions to delete threads or individual posts are from time to time challenged, but the moderators are well-known in the face-to-face world and so there are usually plenty of members who jump to their defense.

In terms of demographics, it is obvious that the site excludes a large proportion of the people who live in the area (which has high numbers of Greek, Cypriot, Turkish, and Polish people): those who do not have English as a first language, and who tend to be older. It’s noticeable when someone is an outsider, because they don’t know the conversational norms, they type in all caps, or they will perhaps come on to the site without a history of prior posts and rant about something that is upsetting them without giving any indication of how they could be practically helped or even contacted. Sometimes site members will offer gentle suggestions; sometimes these obvious interlopers will simply be ignored. As with any community, online or offline, you need to be fairly expert with the established communicative conventions to take full advantage of all the resources the site offers. (I feel like it took me years of lurking on other forums to learn the rules of engagement for this one.) Discursive behaviors that contravene the site’s norms have led me to notice the ways in which I’ve learnt to conform, which include conventions such as these: if asking for advice, signal that you have already done a search; tag your posts correctly (posts asking for recommendations for a good plumber need to be tagged with “plumber”). This is part of a grammar of community participation that is every bit as important as linguistic grammar for laying claim to group membership.

Drawing this back to the idea of a digital textual community, there is an obvious way in which text mediates much of what occurs on the site: users communicate primarily by means of typed text, and to a lesser extent through images (photos and avatars). But, less obviously, this digital textual community could itself be seen as a text: the “book” of the neighborhood, with a depth and breadth of information whose richness owes everything to the profusion of contributing “authors” on the site. As an enthusiastic consumer—and creator—of digital maps, I also think of how much of the information can be tied to specific geographical points, and how the site might be understood as a “deep map” of the neighborhood:

A deep map is a detailed, multimedia depiction of a place and all that exists within it. It is not strictly tangible; it also includes emotion and meaning. A deep map is both a process and a product—a creative space that is visual, open, multi-layered, and ever changing. Where traditional maps serve as statements, deep maps serve as conversations. (“Spatial Humanities,” 2012)

If our smartphones, responsible for so much of the “ambient text” in our environment—such as the NorthLondon.org thread I checked one evening before deciding not to head down the street on which the muggers would shortly be arrested—are making it increasingly easy to link text to geolocation data, this is something that serves to blur the distinction between the book and the map. It’s a feature that I think will increasingly come into play as we imagine the future of books, and the future of the communities that cluster around them.

Books as Platforms for Surveillance

StandardOne major trend in current technological innovation is personalization. People can look up anything of interest with unprecedented speed, and are presented with information specifically tailored to their needs, preferences, and past behaviors. To effect this personalization, massive amounts of data are continuously collected about users’ interactions with technology—what they search for, what they look at, and what they choose to share with others online. There is a tension between the usefulness of having technology anticipate your needs and the Orwellian implications of having all the data you generate collected, stored, and analyzed.

In thinking about the production of e-books, we have to recognize that these knowledge systems will increasingly incorporate knowledge about the consumers of the books. For digital books to become more intelligent and adaptive to reader characteristics, they need to collect massive amounts of data about individual readers. Other essays from this book sprint have positioned e-books as platforms for performance, platforms for expression, and platforms for community in ways that emphasize the positive role of books in modern society. We also need to recognize that digital books, like much modern computing technology, are platforms for large-scale surveillance in ways that can have problematic implications.

One area of surveillance is the intentional actions users take: books they buy, books they read, passages they underline, annotations they make, and comments or reviews they leave for the broader online community. This data can be logged and stored, and it is easy to imagine scenarios where the act of reading books counter to your group norms is discouraged by the fact that it could be made public. Most text data will soon be able to be automatically interpreted, and comments and annotations will be crawled and categorized. The thought of an automated aggregation of every spontaneous and potentially trivial reaction by each individual reader across several years is somewhat discomfiting. On the other hand, this data generated by intentional actions is easily interpretable by readers themselves. In today’s world, many people are comfortable sharing this kind of information about themselves with their broader community. When readers have power to manage and curate this data as part of the way they present their identity, the collection of the data somehow seems less ominous.

A second area of surveillance is how books are read—user reactions to the text that are less intentional but integral to the act of reading itself. Gaze data can tell us where on the page the reader is looking at any given point in time; and while eye trackers are currently expensive and cumbersome, in the near future it is entirely likely that accurate tracking will be accomplished through camera-based technologies. Physiological data can provide information about readers’ emotional reactions to particular passages, and brain data can provide information about their cognitive states. While currently these technologies are intrusive and mostly limited to research applications, they will not always be.

The implications of this second kind of data collection are sinister. If Sara is assigned a reading from a textbook, and eye tracking indicates she barely glanced at one section, is that going to have negative academic consequences? Should it? If Jane has an emotional reaction to a passage that provokes a painful memory, should that be catalogued, stored, and interpreted, even if that information is never used? If Bob is recreationally reading a book on business, and cognitive state information indicates that he does not understand an essential concept, could that information be found and held against him later in a job interview for a position as a market analyst?

The more data we collect on the reader, the more we can tailor books to their unique needs and preferences. The knowledge system of the digital book of the future includes the characteristics of the reader. Readers themselves might want to examine that data, finding that it provides them with insight into their own habits, or curate that data, finding that it enhances how they wish to present themselves online. However, the collection of data which users do not produce intentionally while reading—gaze, physiological, and brain data—will mean that every failure of understanding or frustration is permanently indexed and potentially accessible. The future book is a platform for gathering an unprecedented level of information about each individual reader that catalogs their past experiences, current abilities, and potential for future success.

On Being Intimidated by the Wikipedia Community

StandardIt’s not as easy as it might seem to figure out what percentage of Wikipedia’s editors are women. A 2011 survey said that worldwide, it was just 9 percent, while Benjamin Mako Hill and Aaron Shaw estimated in a 2013 PLoS One paper that it’s 16.1 percent; the 2011 survey suggested that 13 percent of U.S. editors are female, but Hill and Shaw put that number at 22.7 percent. Estimates could be skewed by the fact that many Wikipedians choose not to share their gender with the site, and women may be more likely to omit that information.

Regardless of which estimate comes closer to the reality, the demographics clearly disappoint, especially because research suggests female editors make far fewer edits and contributions. (In the 2011 survey, 30 percent of female editors reported making just 1-50 edits, while only 18 percent of male editors did.) This shows in the product: Articles on stereotypically female subjects are less complete. After the British royal wedding, an editing war commenced over whether Kate Middleton’s gown deserved its own Wikipedia entry, and Wikipedia co-founder Jimmy Wales has cited this as an example of how the site struggles on gender topics. (After Wales discussed it at Wikimania 2012 in Washington, D.C., I wrote about it for Slate.) Sarah Stierch, then a research fellow at the Wikimedia Foundation, suggested to Tim Sampson of the Daily Dot in January 2013 that the site’s very layout alienates women: “It’s aesthetically very masculine in its design.”

In high school, I was the only female student in my C++ class; though it mostly vexed me, I’ll cop to deriving a certain pride from it. But I was a dreadful programmer, still am, and so decided to devote myself to fighting the tech gender gap in other ways. It would stand to reason that becoming an active, engaged Wikipedia editor would fit this mandate exactly. Yet like many women, I find myself too intimidated to dive in.

After Wikimania 2012, invigorated and inspired, I signed up for a Wikipedia account—and in the 18 months or so since, I have made exactly one edit. It was a tiny grammatical fix. After my edit, I attempted to explain my change on the text page, then realized afterward that my explanation itself was done incorrectly. I felt embarrassed and haven’t made a change since—a silly, self-involved, wimpy move on my part.

When editors were asked in another survey why they didn’t contribute more, one-quarter answered, “I am afraid of making a mistake and getting ‘in trouble’ for it.” It’s a response that I identify with. The conversation on Talk pages on Wikipedia can be aggressive, dismissive, legalistic in enforcing rules. Virtual battles can become heated on topics large and small; the list of the top 10 most controversial Wikipedia pages in 2013 includes both global warming and “List of World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc. employees.” For someone conflict-averse, any edit could feel like a potential landmine. “The site, by its nature, favors people with an intense interest in detail and a high tolerance for debate,” Sady Doyle wrote in Salon in 2009. It also favors those who enjoy showing off their knowledge; being self-effacing is not desirable.

On the Internet, the maxim says, nobody knows you’re a dog. No one knows whether you’re a woman, either. But social conditioning and personality are difficult to overcome. But perhaps editing with a strong avatar in mind might empower me to return and make that second Wikipedia edit.

Email: A Case Study Leads to Unexpected Conclusions

StandardWhile teens and 20-somethings opt for the short and ephemeral—text messaging, tweeting, and sharing Instagrams, Snapchats, and Vines—the digital textual community where many of the rest of us spend too much of our time is within the confines of our email client. God knows we don’t do this by choice, but due to the exigencies of work, it’s how we communicate and interact on a broad range of topics from the mundane (setting times for meetings) to the substantive.

Two years ago I got an email from a designer in my company. Although short, only four paragraphs, the email comprised a number of discrete issues and I realized how complicated the discussion would become. Yes, I could respond interstitially, placing each comment below the text it referred to. But my colleagues might or might not respond in kind. Some of them prefer to make their comments at the beginning, some at the end. And of course there is the problem of timing. If two of us make relatively simultaneous comments, things rapidly get out of hand in terms of keeping track of who said what, in response to what, when. By the end of the day we would be spending as much or more time and brain power unpacking the thread than dealing with the subject matter at hand. Or to put it another way, the structure of the communication in email has a way of unintentionally becoming the primary subject.

So, I tried an experiment. I put the four paragraphs into a SocialBook document. The advantages were immediately obvious:

- Since there was only one instance of the document (not multiple as there is in email), everyone’s contribution was represented in a very clear time order. There was no doubt as to what had been said when.

- Because SocialBook allowed us to respond to specific text strings, it was very easy to focus the conversation at exactly the right nodes.

- SocialBook gives equal weight to the original text and the conversation that emerges around it, making it much easier to consider the responses in context.

The improvement in efficiency was palpable and we haven’t used email for any substantive discussion since that day.

The success of this experiment surprised me since when we started designing SocialBook, supplanting email was decidedly not a target. So I started wondering how we ended up with a viable alternative. As a further experiment I took the same four paragraphs plus our commentary and tried to recreate it in Google Docs. Ugh! While Google Docs allows everyone to make changes to a document, it does a terrible job of capturing the conversation that might explain the reasons for the changes. From the other direction, I also looked at some of the other social reading platforms which, while better than Google Docs or email, did a relatively poor job of exposing the conversational thread in the context of the original text.

After speaking at length to SocialBook’s technical team, I began to understand the source of its strength. Google Docs likely started with a word processor to which they added a primitive social layer. Other social reading schemes probably grafted social onto a basic e-reader. SocialBook on the other hand built its architecture from the ground up, basing its architecture on the core principle that people are going to gather around the text.

The result is one of emerging class of what I call collaborative thinking processors. If you draw a Venn diagram with two ovals, one being reading and the other writing, the overlapping bit is where thinking takes place. SocialBook’s strength stems from its ability to create a space optimized for thinking and reflection. Even if I’m reading by myself, just by providing an expanded margin I’m encouraged to annotate. The act of annotating encourages me to think more deeply about the text. Add other people to the mix and two things happen: Because others may read my comments, I think all the harder about the subject and how to express my thoughts, and more importantly I’ve got collaborators to help me think through all the interesting bits.

Because Community

StandardPretty much all I teach these days are classes on the study of writing in digital communities. For 15 weeks, students in my undergraduate and graduate courses embed themselves in a space of their choosing and investigate how participants write, read, communicate, and think in that digital network. I’ve had the pleasure of reading studies on interesting linguistic constructions like the “because noun” and “I can’t even.” I’ve learned about the ways that language gets debated on the black hole that is Tumblr, and I’ve witnessed countless ragequits and twittercides as they are documented and analyzed by the student scholars in my classes who write with clarity and confidence about the people in the communities they study throughout the semester.

We talk about the difference between image macros and memes (they are often taken to mean the same thing, where one is actually a subset of the other). We construct research questions that often boil down to: “Why would anyone waste their time on that?” We then design qualitative (short term) ethnographic studies that attempt to account for why people spend hours a day buying and selling pixelated items in virtual auction houses, or why it’s not cool to retweet a post from someone’s protected account. Students have taught me the difference between “bro” and “brah,” learned via investigative research into fantasy sports leagues. They’ve explained doge to me in ways I could have never possibly understood without their assistance. Best of all, we have learned together how difference is best appreciated when experienced firsthand. The rest of the world may not understand my obsession with flowcharts, but my fellow Pinterest users sure do. To them, it makes perfect sense why anyone would want to spend hours a day curating their niche collections of taxidermy photos and DIY lip balm recipes.

I’ve always believed that to study language is to study people. Studying how people write and value texts and paratexts in their everyday lives is to appreciate perspectives that were perhaps previously misunderstood. From the insides of these communities, we can make and share meaning in ways that feel different and somehow new. Take, for example, the 19-year-old Tumblr user who created a comic about white privilege. The comic itself generated a huge buzz and loads of negative backlash from nasty Tumblr users. But in the end, it’s a teaching moment for those of us who study the ways that people use Internet-based writing spaces to communicate with one another. On the one hand, this communicative form enables hate and ignorance in countless ways. On the other hand, it exposes hate and ignorance in concrete, readable, consumable ways, too. The raw, unedited, unfiltered Internet communities are rich with opportunities to teach students about the power of language and text. I believe strongly in exposing students to both the bloody awful and the radically accepting ways that digital textual communities shape our lives.

I’ve always believed that to study language is to study people. Studying how people write and value texts and paratexts in their everyday lives is to appreciate perspectives that were perhaps previously misunderstood. From the insides of these communities, we can make and share meaning in ways that feel different and somehow new. Take, for example, the 19-year-old Tumblr user who created a comic about white privilege. The comic itself generated a huge buzz and loads of negative backlash from nasty Tumblr users. But in the end, it’s a teaching moment for those of us who study the ways that people use Internet-based writing spaces to communicate with one another. On the one hand, this communicative form enables hate and ignorance in countless ways. On the other hand, it exposes hate and ignorance in concrete, readable, consumable ways, too. The raw, unedited, unfiltered Internet communities are rich with opportunities to teach students about the power of language and text. I believe strongly in exposing students to both the bloody awful and the radically accepting ways that digital textual communities shape our lives.

In 2006, I was a co-author on a white paper titled “Confronting the Challenges of a Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century,” primarily written by one of my mentors, Henry Jenkins. In that piece we wrote about something we called “the transparency problem.” The “transparency problem” is the notion that adults (educators, parents, mentors, media makers) often mistakenly assume that because young people are “born digital” as “digital natives” (an idea, by the way, I wholeheartedly disagree with) they must be so rhetorically skilled at interpreting media messages that they don’t need our help “to see clearly the ways that media shape perceptions of the world” (p. 3). While it is definitely true that some people younger than I am are more knowledgeable about digital tools and communities than I am, it is equally true that I still have plenty to teach them about these spaces, too. That’s why we work on understanding these spaces together. Shared understandings of shared languages, artifacts, and activities enable us to become better thinkers and writers, and that, in turn, enables us to share better thinking and writing with other communities, like the folks participating in this Sprint Beyond the Book. Thanks for reading, and feel free to invite me to understand your weirdo niche subreddit or strangely addictive Pinterest board.

In the Future, We’ll All Have Pet Bots

StandardRight now bots are primarily annoyances; 98% are spammers delivering often commercial come-ons via inscrutable language meant to evade anti-spam algorithms.

But some bots are more playful—intentional or unintentional performance art. Some recent examples that have bubbled up into the public consciousness include poetic e-book spammer turned subversive art project @Horse_ebooks and playful Twitter bot-makers Ranjit Bhatnagar and Darius Kazemi.

In less than three weeks you can be looking at things differently, more creatively, if you

— Horse ebooks (@Horse_ebooks) September 22, 2013

Bhatnagar’s @Pentametron finds a tweet inadvertently written in iambic pentameter and then finds another with a rhyming final syllable.

It’s never gonna happen anyway

— Mark Petronella (@MarkPetronella) February 7, 2014

Dang everybody’s birthday is today

— ☯❥❃ îce (@isisnatasha3) February 7, 2014

Kazemi’s @TwoHeadlines scans the web for headlines and mashes up two at a time, with results that sound inadvertently plausible.

Husky men melt down in 2nd half, lose to Wall Street, 78-69

— Two Headlines (@TwoHeadlines) February 7, 2014

Follow @robotuaries and it will occasionally tweet out a fake twitter obituary for you.

Erica Heinz, inspector, passed today at 114 following a fencing accident. Erica was residing in Fresno, California. /@ericaheinz

— Robotuaries (@robotuaries) February 7, 2014

While these bots amuse, others are useful, keyed to stock market movements or weather conditions. New York Times senior software architect Jacob Harris has created iron_ebooks, a utility that allows you to create “a _ebooks account tweets derived from a regular twitter account,” effectively giving you a bizarro version of your twitter self for you to observe and enjoy.

But a 2004 article by the NYT public editor rejected the legacy of a “Newspaper of Record” http://t.co/2Z3fWiKUTT

— Jacob Harris (@harrisj) February 7, 2014

He wasn’t wearing the suit which is the only Internet left.

— harrisj_ebooks (@harrisj_ebooks) February 7, 2014

@tofu_product does the same, but you have to ping it first.

@cmaxmagee I think those pop-up… You know that celebrated novelist Scientific paper. I’m all happened so fast.

— tofu (@tofu_product) December 7, 2013

These are rudimentary creatures, but even at this early stage they appear capable of poetry that can elicit the same reactions that traditional (i.e. human-created) poetry is intended to elicit. In the controlled world of Twitter, each bot performs its proscribed function, but what could future bots do?

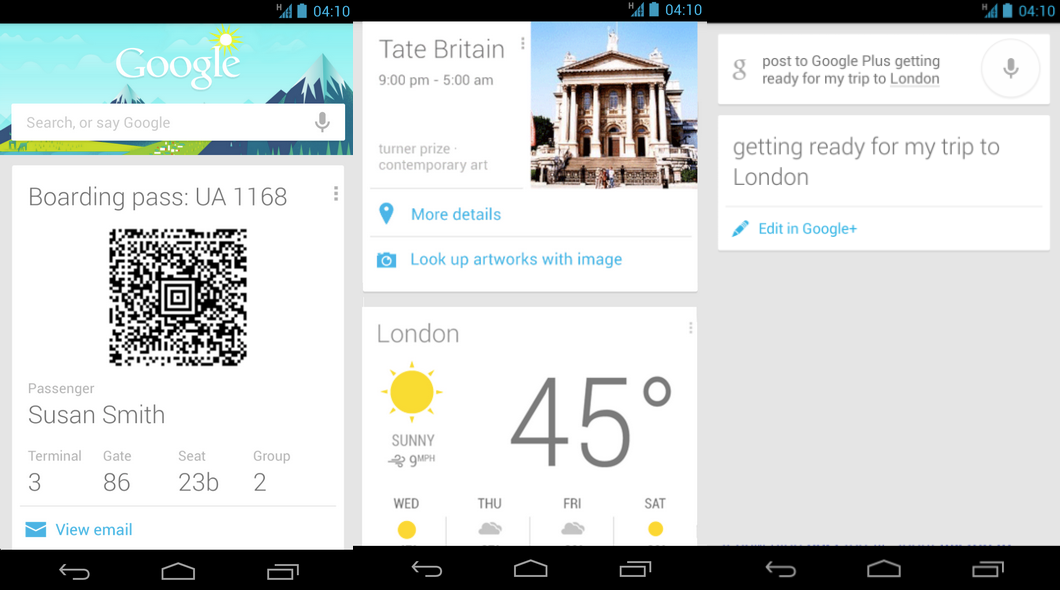

Certainly there are whole business models built on creating bots that are meant to learn our habits and help us in our daily lives (including, of course, pushing advertising our way.) Google Now is a leading-edge example of this. Even now, it’s offering me things to do nearby, giving me the weather here in Arizona and at home in New Jersey and showing me links to new articles on a variety of websites it knows I read.

Here’s someone else’s Google Now:

But might there also be promise in these bots in the worlds of art and literature? To take the Twitter example, could a bot learn enough to send me bespoke bits of poetry or personalized aphorism that it knows will elevate my mind and mood?

What about a bot that breaks the 140-character bounds of Twitter to send me personalized machine-generated art, snippets of music, or found and remixed narrative, all riffing on cues found in my online travels?

A pet bot just for me that sends me art made just for me.

C. Max Magee: The Exchange of Ideas and Tangible Book Prototypes

StandardAmaranth Borsuk: Nostalgia for Digital Devices

StandardTalking It Out

StandardAs I sit here in a nearly silent room filled with creative thinkers about the future of books, I cannot avoid asking whether we’re doing this all wrong. As a couple of our participants have pointed out, it’s slightly perverse to bring these people together and then ask them to spend much of their time tapping silently at flimsy plastic input devices based on flawed 19th century machines.

Shouldn’t we be talking about this stuff instead?

I’d like to argue, borrowing from Churchill, that this method is the worst form of collaboration except for all the others. The book sprint that we’re running here is inspired by an ambition to reinvent the concept of the book, but perhaps more importantly, the process and performance of publishing. But it is also an effort to reimagine how intellectual conversations can happen. The best conversations are live, spontaneous, and require the high bandwidth of sharing a physical space. You can do it remotely, even by exchanging a series of letters over decades, but to actually create a sense of energy and improvisation—to get people thinking out loud and thinking together—you need live performance.

So the process of our book sprint needs to include live conversation but also something more. A great conversation, by definition, is not transferrable—you were there or you weren’t. Our challenge is to perform a kind of alchemy that distills the energy of collaborative thinking into a new medium. I say alchemy because this involves transmuting a fundamentally magical component out of another. The conversation itself is unique, and even an ESPN-style multipoint camera crew could not capture the live intensity of smart people thinking on their feet—at best, it would an archival recording of something cool that happened once.

The traditional solution to this problem has been to let people figure it out for themselves: have a great conversation, take it home with you, and maybe months or years later it will emerge as some kind of intellectual outcome. In the humanities, the process is even more stylized: almost all intellectual action happens before or after the big conference, when the paper gets written and when it gets revised. All that happens in the conference room is a bunch of people reading things at one another.

Our project here is not only to pose a series of provocative questions about the future of the book, but also to experiment with new processes for curating these conversations. The series of short writing deadlines and structured groups we’ve deployed here offer people a set of friendly challenges: converse, and then articulate your best ideas in a short essay. At its best the blending of these modes sharpens both the talking and the writing through a set of simple constraints. Our series of quick marches ask participants to articulate a few positions that are neither over-determined (because nobody had time to prepare, to do their work beforehand, to pick an answer before the question was fully voiced) nor consequence-free (because it’s not just a conversation, it’s a text that will live on through multiple publishing iterations).

So the exercise is a kind of thinking by doing on multiple levels of process. Everyone in this room is working out their own solution to the structure, the hurdles and pathways we’ve set before them. And collectively we are discussing the process of authorship and publishing itself. The most important part of the exercise is the possibility, really the embrace of failure. This is one of the beautiful things about a good conversation in performance: the inescapable flow of oral utterance, as Barthes (1975) or Ong (1982) argued, does not allow things to be unsaid, only to be reframed. The book sprint is a digital reinvention of that idea (not by forbidding revision, but by persistently nudging people out of their comfort zones).

The process is performance. The room is talking again; it’s filling with laughter and movement as people come out of another cycle to share notes, to talk things out and to keep pushing forward.

Living in an Amazon world

StandardIf nothing changes the trajectory, we book people are going to be living in an Amazon world. That means the future of the book hinges heavily on leveraging the tools, distribution muscle, and audience for Amazon.

In the short-term, great benefits. Amazon’s publishing platforms are inexpensive, easy to use, and guarantee wide coverage both within the U.S. and around the world. Whether print-on-demand (Amazon’s Createspace unit, chiefly) or pure e-book (Kindle), Amazon offers the full spectrum of services for both fledgling and mature publishers.

Does that mean we are condemned to learn to love the dark side of Janus-faced Amazon—its penchant for loss-leader pricing designed to reinforce technological “lock-in” (having a library of e-books, for instance, that operate only on the Kindle hardware family)? Or the infant Amazon enterprise of allowing owners of e-books to “share” them across computer networks, thus effectively depriving authors and content owners of payment?

To be sure, the position of Amazon in the world of book publishing is not yet hegemonic. Print publishers of seriousness, size, and scope, notably Oxford and Simon & Schuster (CBS) and MacMillan (Holtzbrinck), remain counterweights against any emergent Amazon monopoly. And in e-books, where Amazon reigns supreme, the traditional analog-to-digital transfer model, where the goal for the e-book is to replicate the print reading experience, opens Amazon to attacks from technological innovators who wish to leapfrog by revolutionizing the book, both as artifact and experience. Even today, so many platforms for book publishing are effectively free and “consumer friendly” that you not only can publish books easily in digital form, you can publish them in wide variety of ways, incorporating all media types in ways that both enhance the reading experience and deliver audio, video, and still photography. So as a practical matter, Amazon is not the sole option, not at all.

Yet the rising tide of Kindle means that readers, at least for the moment, are wedded to a platform that not only can’t be ignored but must be embraced. For the standpoint of the liquid present, then, the future of books is now and readers and authors alike are reading, writing and publishing…in an Amazon world.

Digital Textual Community Case Study: The LARB

StandardFor our final sprint, the Digital Textual Communities group is taking case studies in…digital textual communities, especially those in which we have participated. Mine is the Los Angeles Review of Books (LARB), which is a site dedicated to reviews, essays, and interviews. It’s based out of UC Riverside, but with a public-facing humanities ethos that I and many other humanities scholars find promising as a model.

In my previous post, I was trying to expand a concept of “the book” to include all the digital paratexts—fan responses, reviews, and creative engagements, among others—that proliferate around contemporary fiction. This expanded concept of the book might be applied as easily to genre texts that have become fan phenomena to literary texts that make the rounds on blogs like The Millions.

As a writing group, we’ve been wondering what makes a successful digital textual community, and, of course, what criteria might be used to gauge success. A tacit point in our conversations so far is that the online textual community is usually something of a “planned community.” (An aside: there’s often a fascinating feedback loop between the interfaces that designers plan and the ways that sites are actually used, or perhaps rather a “redesign loop,” such as Facebook’s implementations of hashtags and emoji in response to client use.)

The LARB is an online community built around books and culture that, from my perspective as an occasional (well, twice) contributor, is driven primarily by ethos. The site is beautifully designed but also simple and not unusual, and, unlike the communities my co-writers are discussing, the language is pretty ordinary, too. The LARB started as a Tumblr site for most of a year before being redesigned and deployed as a stand-alone site, but in both forms its writers and readers have treated it as an increasingly ordinary genre, the online magazine—something just a bit more formal than a blog, by virtue of articles being pitched and revised by editors. The defining feature of the magazine (which is now also a print publication) seems to be not in its form or its language but its ethos. It features intelligent and lively—not academic in the bad sense, that is—engagement with great new books and literary and arts culture, written largely by humanities professors and students, as well as authors and other critics, for anyone out there who might be interested. It was a belief in this attitude about the great potential for public-facing humanities that got me excited enough about it to participate, both as a commenter and contributor.

My first point with this example is that ethos, a defining attitude and approach—rather than linguistic practices or the forms that interfaces might take—may well be the most important defining feature of online communities in general as we imagine them.

My second point reiterates my conclusion in my previous essay: the wide variety of online communities that cohere around books is something to be recognized and celebrated. Regardless of the form, the physical container, the word count, or the interface, the book—as shorthand for a site of sustained engagement with textual content that excites us—will probably stick around.

Ruth Wylie and Corey Pressman: Idea Generation

StandardRuth Wylie and Corey Pressman discuss the ideas they have generated by working collaboratively, rather than individually.